The Reproductive History of American Women: The First Half of the 20th Century

The growth of anti-abortion movements

Welcome back to my series on the history of women’s reproductive health in the United States. Since it’s been a while since I last posted, feel free to revisit my previous post explaining this history from a 19th century standpoint. The TLDR — at least toward the end of that post — is that a movement rooted in the supremacy of educated doctors over community midwives and fears of a growing population of undesirable immigrants and their children resulted in limitations on women’s ability to pursue reproductive recourse.

This post will go into detail about what happened with women’s reproductive health in the 20th century. Given that a lot has happened, this post will only focus on the first half of the 20th century.

By the end of the 19th century, the most motley of stakeholders — the American Medical Association, anti-obscenity activists, and even conservative women’s groups — publicly condemned the practice of abortion.

This led to a nation-wide ban in 1900.

At the turn of the 20th century, women’s inferior place in society was even more firmly cemented. This was even more true for women who were formerly enslaved and their descendants. However, there was a particular focus in monitoring the bodies and movements of a growing class of young women — working white women living far from their parents working in factories, secretarial pools, and other places. This increase of young single women in urban populations also coincided with public demonstrations for women’s suffrage, further highlighting an increased consciousness about the role of women in American society.

Caption: Young women working in a Colt manufacturing company in Connecticut.

Source: Library of Congress.

At least six years before women gained the right to vote in 1920, reproductive activist Margaret Sanger coined the term “birth control” for the first time. Throughout the 1910s, Sanger was committed to pushing against the 1873 Comstock Act, which prohibited the purchase of contraceptives — which the Act defined as “obscene material.”

Until 1930, women living in these cities were able to obtain contraceptive services and then-illegal abortions more freely. This was because patent medicine companies disguised abortion medications as remedies for women’s health issues to evade strict advertising laws. However, doctors could no longer legally perform abortions.

Given that abortions were illegal during this time period, abortion practice continued but in unclean and unsafe environments. According to the Guttmacher Institute, almost 1 out of every 5 recorded maternal deaths occurred due to botched illegal abortions. Until the mid 1950s, laws and policies such as the Comstack Act prosecuted abortionists and harassed women who tried to access abortions.

In 1959, a group of liberal legal professionals from the American Law Institute advocated for more flexibility in the then-current laws and policies governing reproductive rights. In particular, they advocated for abortion exceptions for women who were raped or whose fetuses were experiencing abnormalities. This was further brought in to the cultural imagination due to the introduction of thalidomide (a pill prescribed to pregnant women experiencing nausea that inadvertently caused severe defects) and German measles (resulting in children being born with severe deformities). The photos of helpless white middle-class mothers with their ill children spurred the feminist movement in its infancy, which emphasized that women need to have reproductive control to be full citizens in American society. With sufficient momentum, several states reformed their state-wide abortion policies, including Colorado, California, and New York.

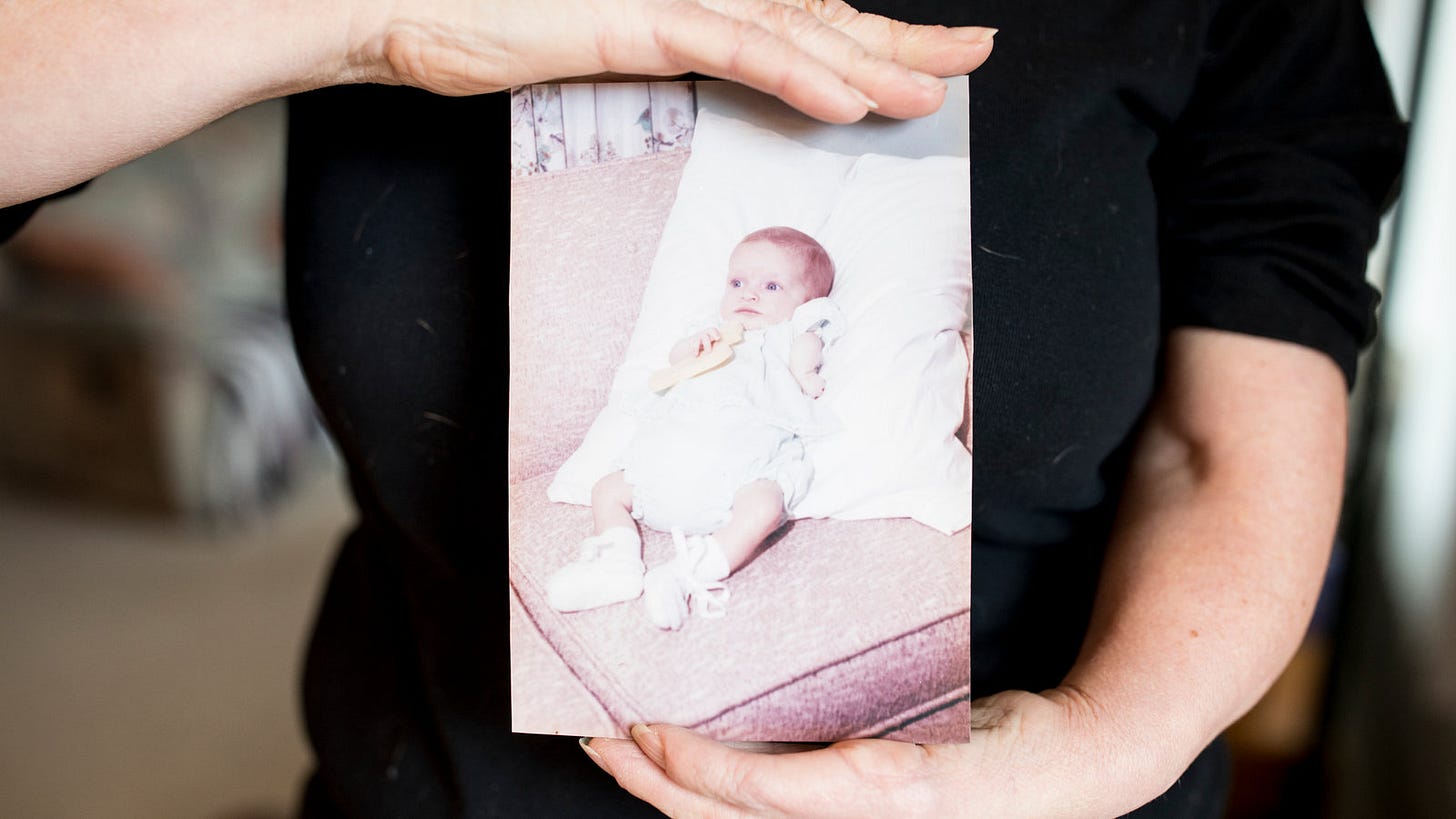

Caption: A photo of an American thalidomide survivor in the 1960s.

Source: The New York Times

Seeing how quickly these changes were occurring — after all, many of these changes occurred in the 1960s — anti-abortion supporters quickly mobilized. Terming themselves in support of “the right to life,” antiabortion activists — comprised of predominantly Catholic but also other religious leaders — formed the National Right to Life Committee. This group came together in 1968 and pushed against state-level abortion reform, and experienced some success in Michigan.

Tensions came to a fever pitch in the early 1970s, as antiabortion groups sought to center the fetus and decenter the woman carrying one. By using language that treated the fetus as a child, antiabortion activists sought to compare abortion across the country as a mass genocide of the unborn. As such, legally, the movement used the framework of civil and human rights in favor of the fetus.

Then, in 1973, the court case that has defined abortion policy in the United States reached the Supreme Court.

Roe v. Wade.

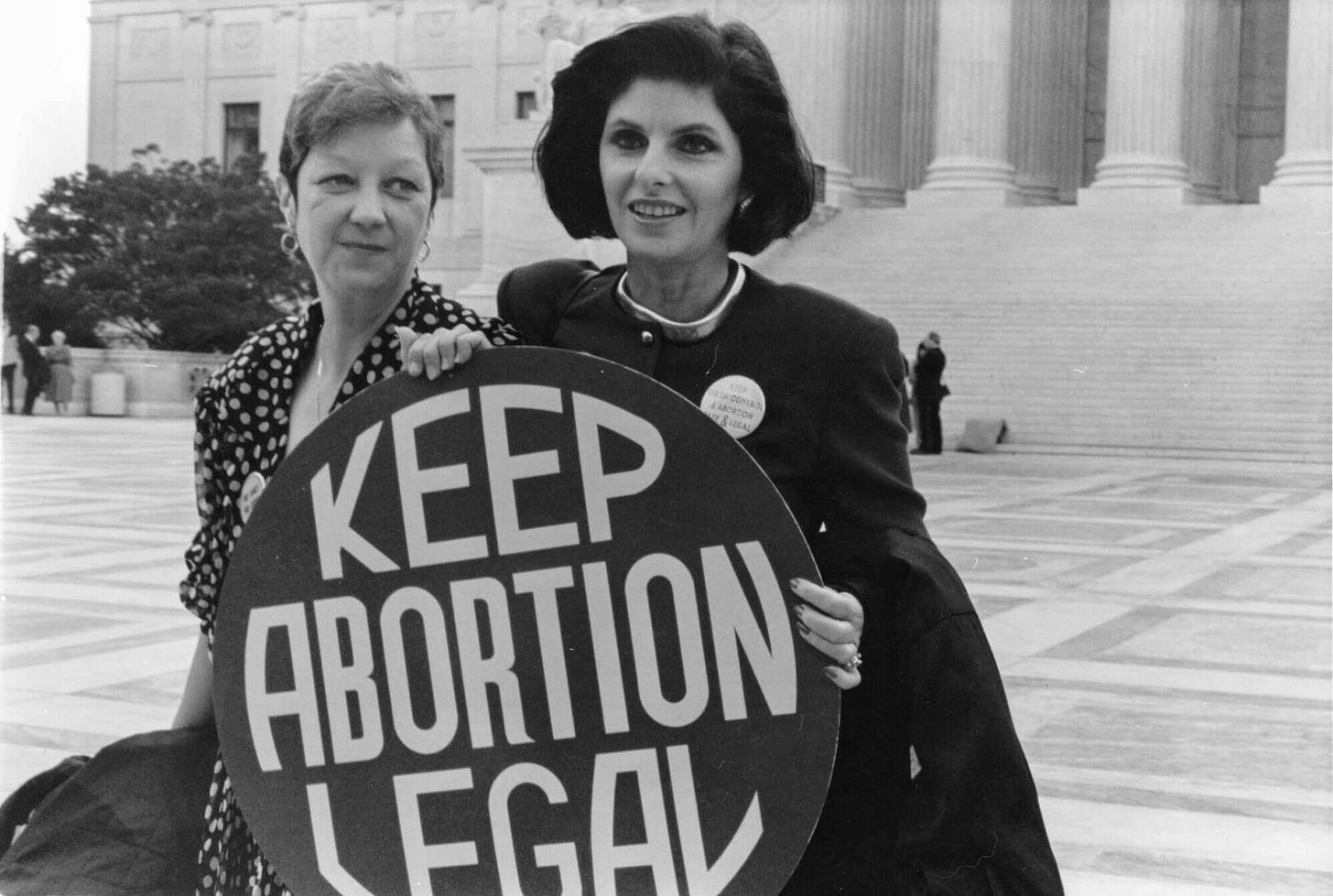

Caption: Norma McCorvey (“Jane Roe”), the plaintiff of Roe v. Wade, with her lawyer, Gloria Allred, on the steps of the Supreme Court

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Which I will cover in the next article!